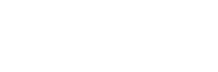

Lena works as a music teacher in Yekaterinburg. She’s interested in Mari culture and collects and sings Mari folk songs. Lena used to come to the Mari Karshi village in the Sverdlovsk region to visit her mother on holidays and long weekends, but she stopped when her daughter was born because she feared that the villagers could cast an evil eye on the baby.

We came up with the idea of the project “Ural Mari. No death” in 2016. Over a period of a year and a half we travelled through almost every Ural Mari village of the Sverdlovsk and Perm regions, talked to the locals, recorded videos, took photos and conducted interviews. We wanted to understand how the contemporary village Mari are living the disruption of their traditional culture that is so inevitable in an era of globalization. The primary distinguishing factor between the traditional and the

Elena Ivanova, music teacher, Yekaterinburg. Collects and reinterprets Ural Mari songs.

modern ways of living, as well as between urban and rural lifestyles, is the maintenance of a relationship with one’s ancestors. Because of this, we made it our goal to see and document the ceremonies, rituals, dreams and beliefs related to the dead. Furthermore, we extended our subject matter to include the whole spectrum of magical practices — from the traces remaining from ancient mythology to modern esoteric influences that come from TV and newspapers.

We came up with the idea of the project “Ural Mari. No death” in 2016. Over a period of a year and a half we travelled through almost every Ural Mari village of the Sverdlovsk and Perm regions, talked to the locals, recorded videos, took photos and conducted interviews. We wanted to understand how the contemporary village Mari are living the disruption of their traditional culture that is so inevitable in an era of globalization. The primary distinguishing factor between the traditional and the

Elena Ivanova, music teacher, Yekaterinburg. Collects and reinterprets Ural Mari songs.

modern ways of living, as well as between urban and rural lifestyles, is the maintenance of a relationship with one’s ancestors. Because of this, we made it our goal to see and document the ceremonies, rituals, dreams and beliefs related to the dead. Furthermore, we extended our subject matter to include the whole spectrum of magical practices — from the traces remaining from ancient mythology to modern esoteric influences that come from TV and newspapers.

This is how our Ural Mari expeditions began — with an understanding of a Mari village not as just a small world where everyone knows each other for generations back, but rather a closed and magical space that has its own rules. You can visit the village any time you want, but if you grew up in a city the Mari magic of local spirits, communication with dead relatives, and the ability to experience precognition and to receive messages from the invisible world through dreams — all of this will remain mere folklore to you.

As urban citizens, we try not to think about bad things. Our whole culture serves the desire to forget about death — which is why it is always so sudden and so treacherous. But for the people of the Mari village, the line between the world of the living and that of the dead is much more democratic. From their point of view, a person has an active afterlife after their death. A funeral is a special ritual to help the deceased to make their way safely to the afterlife and to find their place there easily. After death, they shouldn’t bother the living with complaints, to ask for favors, or, moreover, to bring them bad luck. At funerals, the following phrase is recited: “Go, and don’t bother us anymore.”

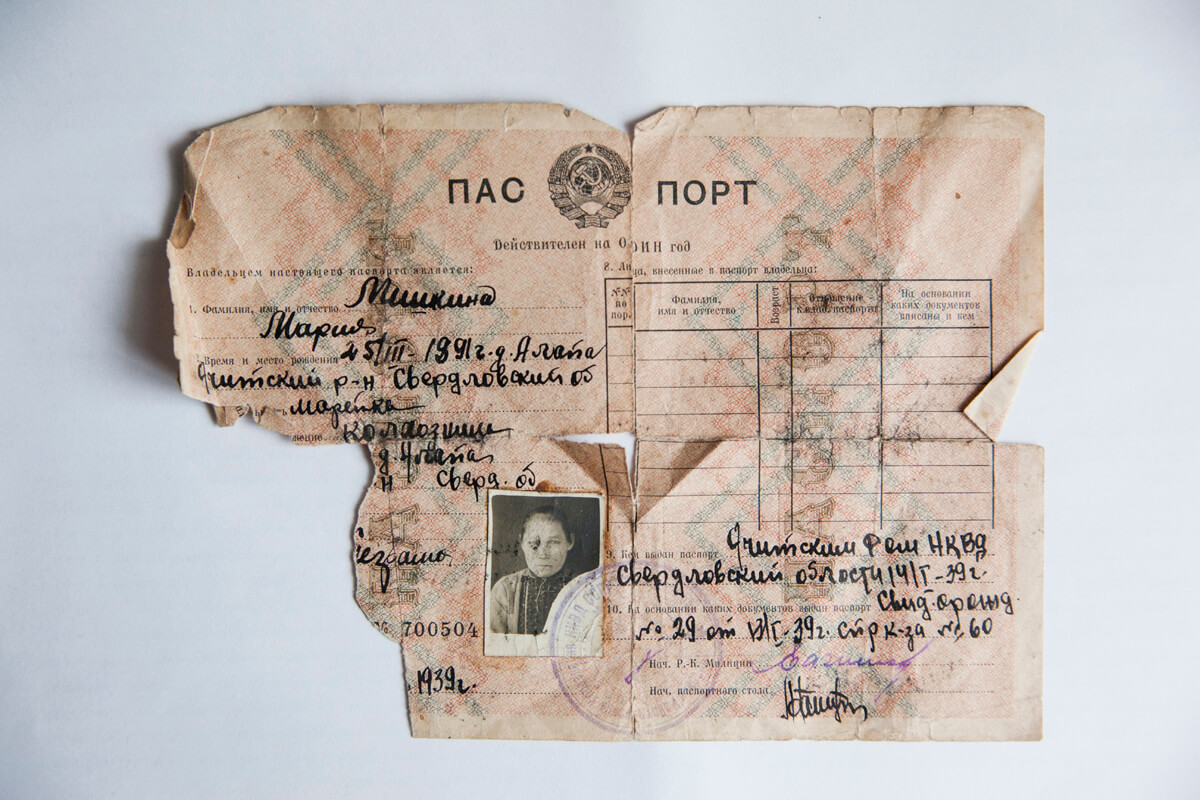

In order to ensure a smooth transition into the afterlife for the deceased, the elderly Mari prepare everything beforehand. In Kurki, a village in the Sverdlovsk region, we met with Anyai Semenova, who had everything prepared for her own funeral long ago, and who even complains that none of her deceased relatives call her to join them. In her trunk she stores for her own use in the afterlife shawls, dresses, a blanket and three white threads — to

“swing on a swing there”, as well as a bottle of vodka that she will give to her deceased mother. In the pocket of the festive yalan (caftan) that she will be buried in, Anyai keeps a bag of coins. She has prepared this yalan for her funeral — dressed in this garment she will be able to transfer money to the other world.

In order to ensure a smooth transition into the afterlife for the deceased, the elderly Mari prepare everything beforehand. In Kurki, a village in the Sverdlovsk region, we met with Anyai Semenova, who had everything prepared for her own funeral long ago, and who even complains that none of her deceased relatives call her to join them. In her trunk she stores for her own use in the afterlife shawls, dresses,

a blanket and three white threads — to “swing on a swing there”, as well as a bottle of vodka that she will give to her deceased mother. In the pocket of the festive yalan (caftan) that she will be buried in, Anyai keeps a bag of coins. She has prepared this yalan for her funeral — dressed in this garment she will be able to transfer money to the other world.

Anyai promises to dream to her daughter after her death and tell her what she saw in the other world.

Anyai has thought through all of the details, including the commemoration that she wants to be held in the village refectory. She doesn’t know anything about what the “afterlife” looks like or how people live there. We asked how much money you need to take there and why you would need it at all, but she always answered, “They say you have to,” or even, “How should I know?!” But Anyai is sure that the coins are needed,

and not paper currency. The value of money changes in the transition from this world to the other: it is not worth as it would be established in this world that counts, but rather the fact that the pieces are metal, and therefore clink against each other. Anyai promises to come to her daughter’s dream and recount everything that she sees in the afterlife.

It is important to maintain contact with the deceased after their funeral. There are special holidays dedicated to this, during which the dead return to the village as guests, but otherwise dreams are the main medium that serves this purpose. The main Mari holiday is called Kugeche, or the Mari Easter. Kugeche falls in the springtime and is celebrated over a few days, which are strictly arranged – on certain days it is forbidden to work or to stoke a furnace, while on others one must bathe or cook. The peak of Kugeche is on a Thursday, during the time before sunrise when the dead relatives visit their homes and they are to be fed their favorite food along with eggs, flat bread and home-brewed spirits.

At the beginning of summer, during the week before the orthodox Pentecost, after having spent a few weeks in the village, the deceased are escorted back to the cemetery and Semic – the parental day – is celebrated. This ritual is familiar to many non-Mari citizens, because it is the best preserved: one vodka shot and a piece of bread on the grave – these are the traces of Semic, which was celebrated not only among Finno-Ugrians but among Slavs as well.

Today the village Mari celebrate it actively: the bread is crumbled onto the grave, onto which home-brew is then poured, which is then followed, if the deceased smoked, by a lighted cigarette.

As we observed the relationship of the village Mari with their dead relatives, we understood intuitively which traditions and rituals were more ancient and which ones were a result of a cultural synthesis. Kugeche and Semic are obviously amongst the older celebrations that continue to exist in Mari villages even in the era of television, mobile networks and internet. We are happy to have discovered them in such a preserved way, but our object, in traveling hundreds of kilometres through the Sverdlovsk and Perm regions, was not to find something ancient. Our goal was rather to find new meanings in the old rituals that we encountered, to observe the ways in which the old culture answers to the challenges of a new history. And indeed, the 20th century history has corrected the village annual calendar.

“My father-in-law was a war veteran, he drank a lot,” Natalia Shumatova, from the village Artimeikovao, told us. “And his daughter once said to him, ‘Once you die I will come to you on the 9th of May and pour out the whole bottle of vodka on to your grave!’ And that’s what she did. Now she comes there every year.” This is how we found out that the deceased war veterans are fed separately – on Victory Day, which falls between Kugeche and Semic.

“My father-in-law was a war veteran, he drank a lot,” Natalia Shumatova, from the village Artimeikovao, told us. “And his daughter once said to him, ‘Once you die I will come to you on the 9th of May and pour out the whole bottle of vodka on to your grave!’ And that’s what she did. Now she comes there every year.” This is how we found out that the deceased war veterans are fed separately – on Victory Day, which falls between Kugeche and Semic.

Communication with the deceased is maintained as long as the person is remembered – for two to three generations. In addition to the holidays dedicated to the remembrance of the dead, another mode of communication is practiced, one that is not very stable, but is more intimate: the dead are often seen in dreams. They come to complain about oblivion, to ask to be fed, to warn about danger or, sometimes, to beckon the living to join them. We collected quite a few of such stories during our expeditions. One descendant would often ask his widow to bring him food – seven flat breads, mushrooms, cabbage. Another complained to her children of a wire that had trapped her – the false flowers that were installed at her grave needed to be removed. A third said that he was lying in water, meaning that the relatives ought to cry less about him. And a fourth appeared with hair curlers and a comb, which was understood as a request to bring these objects to the grave, to give them to her.

“But they come in dreams if you don’t feed them!”

Funeral rituals, the feeding of the dead on holidays and upon their request – these are inherit aspects of the country life of the modern Ural Mari. There is no such strong connection with the ancestors amongst the Mari living outside of the villages. The dead don’t travel around the world and don’t become nameless ghosts as they do in films or in comic books. They lie in the village cemetery, occasionally visiting their former homes, but they don’t leave the magic territory of the village.

Household magic, or the “everyday routine”, works in the same way, according to the stories we collected. During our expeditions we asked the Mari if magic exists and if we could see the actual magicians who practice it. Occasionally they showed us, allowing us to record a “fast foot charm”, a belt fortune-telling, and a healing process that was a synthesis of Mari magic and modern esotericism. But for the most part people didn’t want to answer our questions about magic. They got shy, and tried to change the subject. One interview clarified the situation a little bit. Valerij Kandybaev, an activist of the Mari culture Renaissance from the village Mari Ust-Mash, explained that, before, there was no magic – just “people who knew things”. The idea of magic, he said, probably came from television, “from Russians” – meaning from the outside world. “Some people did some good things,” he said, explaining what we called magic but refusing to use the word. “And then they do this… this who knows what”. The problem seemed to be in the Russian word “magic”, which they associate with black magic – the evil eye, evil spells, curses and “kil” (abscess) and everything that the Mari are afraid of, but do nevertheless believe in. Whether or not the Mari always differentiated between black and white magic is not clear, but the difference exists today. A practicing witch doctor, Manya Yanekova from the village Malaya Tavra, offered an interesting classification of white and black. According to Yanekova, you can’t charm a man into going away, but you can bewitch him, to draw him to you, because the latter is done in the name of kindness.

The Mari did not have witchcraft before, there were “people who knew”. And it most likely came from the TV.

The esoteric, that is, the sort of magiс practices that came from mass media in the 1980s and 90s, holds a special place in the daily routine of the Mari. The outgoing generation of traditional magicians was replaced by psychics, both from the village and from cities. A great deal of literature, let alone newspapers and television programs, have been dedicated to the “folk” curing ways, evil eye protections, manipulations of “energetic fields” and other magical practices synthesized out of ethnographic materials, scientific researches, eastern religions and so on.

Towards the end of the 1980s, the so called “traditional Mari religion” came to the Ural region. This term appeared at the beginning of the 1990s, originating in Marij El.

Ural Mari consider Marij El to be their historical homeland and try to follow the norms established there. At the annual prayer in the holy grove not far from the village Sarsa, the Mari pray to the main god Kugu Yumo (whose full name is Poro Osh Kugu Yumo, or Big Kind White God), as well as to the gods responsible for the main forces of nature: the god of fire, the god of fog, mother of the wind and mother of the moon.

However, the reconstruction of the Mari religion has not taken root in everyday life. Mari people often find it difficult to list the gods of the official pantheon, because they prefer to pray to closer spirits: water and wind, the master of the village, the master of the cemetery and simply nature in general. And, on special occasions, to Keremet, the Mari analogue of the devil which, unlike its Christian colleague, does not represent absolute evil. Moreover, there are special locations where Keremet is said to reside, often referred to simply as “keremet” and usually located in ravines and other dark places. Previously, there were keremets near every village, just as each village had a sacred grove. Today, there is only one operating – reconstructed – prayer grove in all of the Urals, and there are very few remaining keremets.

In order to pray, the Mari do not need special words. It suffices to pronounce one’s wishes in the Mari language. “We are pagan,” one villager from Mari Karshi, Tatiana Dmitrieva, told us (“pagan” in Russian also means something like “linguistic”). “We pray with words.” We asked often whether the prayer would be effective if pronounced in Russian, and asked for a translation of prayers. The Russian translation almost always resembled an orthodox prayer.

Mari religious cults have been absorbing different features of Christianity since the time of the first Orthodox missionaries. Many Mari were baptized at the beginning of the 20th century, with a huge wave of baptisms taking place in the early 1990s. Orthodoxy served as a quick solution to a generalized identity crisis. “It’s a pity that we knew so little about our own Mari tradition in the 90s,” explained Natalya Shumatova from Artymeikova village.

“Many were baptized then, because it was unclear where else to turn.” Today, the Ural Mari of the older generation don’t cross themselves in order not to betray their ancestors, but they often pray to the Mother of God and Nicholas the Wonderworker. In the village of Sarsa, we were told: “God is one — faiths are different.” In Nizhny Bardym, villagers pray not only to the Mari, but also to the “Russian gods”: Christ, the Mother of God, Saint Nicholas. And in Mari Karshi they demonstrated to us how an unbaptized Mari must make the sign of the cross: to the front, to the back and to the side.

The Mari started moving to the Ural region from Povolzhye, the territory that would later officially become the Mari El Republic, in the 16th century. The first wave of migration was connected to a crucial moment in the history of the development of the Russian state: in 1552, Ivan the Terrible seized Kazan. Amongst the Turks and Finno-Ugric people who had been living as one in the Kazan Khanat territory, some were unhappy with the new patronage and the prospect of Christianization that accompanied this annexation. Amongst the rebels were the Mari, known as the “cheremis”, or Cheremises, until 1918. For 30 years following the fall of Kazan, the Mari and other Finno-Ugric people fought in the Cheremis War (also known as the Tartar Rebellion), only to be ultimately defeated and forced to sign a pledge of allegiance in Moscow.

For the next few centuries the Mari were forbidden to work as blacksmiths or to live in the cities as a result of government efforts to avoid giving their new subjects an opportunity to make weapons and rebel. Those who converted to the Orthodox church had better chances of integrating into Russian society – of receiving an education and living in the city, of avoiding the elevated taxes otherwise imposed on them. Those who preferred their traditional faith stayed in villages. The most radical went further away from the central government, to the Ural region, which contributed to the preservation of the traditional religion even throughout the Soviet Union.

Over the next centuries, the Mari were forbidden to engage in blacksmithing and settle in cities – the government tried to completely deprive new partials of the ability to forge weapons and rebel.

The Revolution and the Civil War were no less of an ordeal for the Mari than the capture of Kazan in the 16th century by Ivan the Terrible or the peasant revolts of the 18th century. Some Mari fought alongside the Reds, while others chose to proceed according to the idea that any change brings misfortune.

In 1918 the First All-Russian Congress of the Mari people took place. Amongst others, a decision was made to renounce the offensive name “cheremis”. Mari language newspapers were founded. In 1920 the Mari Autonomous Region (since 1992 republic Mari El) was formed, giving the Mari their own territory for the first time in history (though many would continue to live outside of it). But ten years later Soviet national politics would suddenly change. With the onset of collectivisation, religion was banned, and many Mari priests – karts, molls – were repressed.

After the war, the Mari agricultural order was not much different from the rest of the Soviet villages, with one exception: among the Mari peasants there were many who retained the faith of their ancestors even during the peak of religious persecution. Apart from a short remission during the Second World War, when representatives of all faiths were allowed to pray, the religious life of the Mari under Soviet power was held secretly and the believers risked reprisals.

T

oday the Mari villages are in a state of transition. The Kolkhoz have long been disbanded, their property abandoned or privatized on disputed conditions. There are few private farmers left, often those who appeared independently and not on the remnants of collective farm property. The few who open new farms are sometimes the only employers in the village, aside from those who own shops and budget organizations. An undermined rural economic structure is combined with the poor provision of villages. As a result, keeping cattle turns out to be almost more expensive than buying meat in the store – if it is even sold there.

Those few who open new farms are sometimes the only employer in the village, in addition to shops and public sector entities.

New farmers not only experience restrictions from the state, but also hostility from the village, sometimes as a result of the ambiguous privatization of the 90s.

During our expeditions, we met one truly successful farmer who not only earns enough for his own family, but also supports others. Vladimir Aymetov, from the village of Sarsy-2, is the son of the state-owned party organizer, a former real estate salesman, now the owner of a large private enterprise and a philanthropist. Aymetov owns a dairy farm and a grain elevator. He rents allotments of land from locals, and pays the rent with a portion of the crop. He supports the local school and kindergarten, repairing public buildings at his own expense. He provides financial support to both the activists of the revival of the Mari culture and the Orthodox monastery of St. Zosima, the restoration of which he initiated himself. Additionally, he conducts excavations of mass graves of starvation victims from the thirties.

Vladimir Aymetov tells his life story as the son of a state farm party organizer, becoming an entrepreneur and, ultimately, the owner of the largest farm in the area. Sarsy Village, Sverdlovsk region.

Providing support for the Mari holidays and customs is a conspicuous activity for an outsider like Vladimir Aymetov. He not only initiated the revival of collective prayers and financed the construction of the bathhouse at the foot of the sacred grove, but also endorsed a new kart – Leonid Kanakaev, an agronomist who continues to work on Aymetov’s farm. In addition, Aimetov organized his own ancestral grove, in which Kanakaev holds alternative prayers. Amongst the trees of this grove is one named for a certain Mykola Yumo. That is, Nicholas the Wonderworker.

In many villages we were told told that in the 1960s and 1970s Mari traditional clothes and any other Mari attribute was considered by young people to be a sign of backwardness and crassness. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, along with new trends from Mari El, the revival of the Mari culture as a fashion made its way to the Ural Mari villages. For the first time in a long time, the Mari wore costumes to perform at festivals organized in Mari El. By this time, some traditions – such as the holding of prayer in a grove, or the pantheon of gods – had already disappeared, but others still remained: the Mari language and Mari songs, with which the inhabitants of the Urals began to go to performances in Mari El.

Contemporary Mari culture is a synthesis of old and new cults: Orthodoxy on the one hand, and New Age and the primitive faith in the animation of nature (animism) on the other; stories passed down from generation to generation and information from the Internet; ethnographic descriptions written by the Mari missionaries of the 19th century and modern reconstructions of what is “Mari” from magazines published in Yoshkar-Ola. For the Ural Mari themselves, there is nothing strange in this combination. On the contrary, we often heard the opinion that “pagan” – polytheistic, oral, not fixed in writing – Mari culture is fundamentally tolerant and open to any influences. “One God, different faiths,” we were told in the villages.

Sometimes in the process of this synthesis new cults are born. We saw such a process in the village of Andreikovo in the Sverdlovsk region. In the early 2000s, the villagers became interested in local toponymy and began asking the elders why there was a place called Bogatyrsky Log (“Hero’s ravine”) on the other side of the river, on the mountain adjacent to the village cemetery. One Mari recalled the stories of her grandmother, according to whom a Mari hero, Patyr, died in this place. He died, according to the stories, protecting the Mari from enemies, but the oral tradition did not preserve any indications of a historical event. Interest did not subside and the local historian Valery Gankin took up the question of Patyr. Comparing the different stories of village grandmothers with books on the history of the Urals, Gankin concluded that Patyr, who died in the ravine, was the leader of the Mari, who fought alongside Tsarist forces against the rebel Bashkirs.

“That’s how in the village of Andreikovo,” the local historian writes on his website, “they will show you the mountain, the log, and the place where the brave resistance leader named Patyr (hero) is buried… Local sources say that the right to the ancestors of the local Mari people defended life in victorious battles in 1736–39.” There is no evidence of a connection between local toponymy and real historical events. Moreover, from the historical works of Karamzin and other historians, from the decrees of Alexei Mikhailovich and other sources, we know that the Mari could have also fought against Russian troops. Nevertheless, the story of the battle of Patyr with the Bashkirs became extremely popular in the village of Andreikovo. In the tradition of patyr worship in Mari El, locals dragged a huge boulder into Bogatyrsky Log, on which they wrote the word “Patyr”. And now, during Semic, the whole village, having fed the village relatives in the cemetery, rises to the next mountain to feed Patyr, as well as to touch the stone and make a wish.

And now, during Semic, the whole village, having fed relatives in the cemetery, rises to the next mountain to feed Patyr, as well as touch the stone and make a wish.

The final dialectic

It is not known which of the rites and traditions that exist were typical for the Mari in ancient times, which arose as a result of the close contact with the Turks in the Khazar Kaganate, the Volga Bulgaria or Kazan Khanate, with the Slavs from the the 16th to the 19th centuries, and which appeared in the 1990s as input from Mari enthusiasts in the historic homeland, the Republic of Mari El. During our expeditions, we did not always manage to overcome the temptation of distinguishing “real” practices from late influences, “authentic” Mari rituals and Orthodox elements, etc. However, the result of the project “Ural Mari. No death” became a clear understanding that the Ural Mari culture is equal to itself and does not boil down to a history of influences.

But that’s not all. The local experience of the Ural Mari can give a key to understanding the global problems of ourselves – urban residents with uncertain identities, complex family histories and chaotic belief systems.

Translated from Russian by Alexandra Rumyantseva, Arianna Sullivan.

All rights reserved © 2019. Allowed to use materials with a link to the site and the Khamovniki Foundation.

text, video:

NATALIA KONRADOVA

photo, video:

FYODOR TELKOV,

ALEXANDER SORIN

photo: ALEXEY ERSHOV

video: ANATOLY KURLYAEV

website design: ANASTASIA LEBEDEVA

web-design: ILAY FIGLIN

project partners:

Novosibirsk State Museum of Local History And Nature

Boris Yeltsin Presidential Center Foundation

All rights reserved © 2019. Allowed to use materials with a link to the site and the Khamovniki Foundation.